|

Scale effects |

|

Introduction |

|

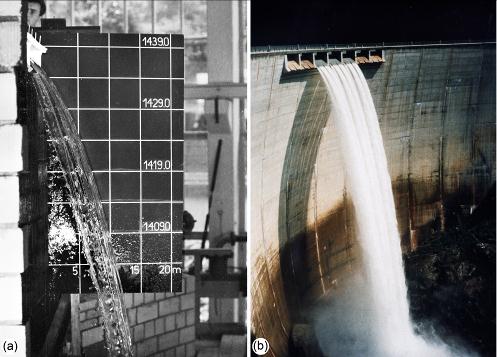

Scale effects arise due to forces which are more dominant in the model than in its prototype. This results in deviations between the up-scaled model and prototype observations. Figure 1 shows how scale effects affect the jet over an overflow spillway at scale 1:l (delta) = 1:30 (l (delta) = lengthPrototype/lengthModel). While the jet trajectory between model and prototype agree well, the air concentration in the jet differs considerably and would be misleading if up-scaled from the model to its prototype. Scale effects can potentially result in an inappropriate design and failure of the prototype (cf. Sines breakwater in 1978/9). Dr Heller has investigated scale effects in various phenomena, including landslide-tsunamis and ski jumps, and he wrote several review articles about scale effects in general (Heller 2007, 2011, 2017). |

|

|

|

Personal research website of Dr Valentin Heller |

|

Review articles |

|

Fig. 1. Overflow spillway of Gebidem Dam, Valais, Switzerland: (a) model at scale 1 : 30, (b) prototype in 1967; the air entrainment of free jet differs considerably due to scale effects (Heller 2011) |

|

Selected publications |

|

Journals Roy, D., Begam, S., Heller, V. (2026). Experimental insights into scale effects in 3D granular slides. Natural Hazards (submitted). Catucci, D., Briganti, R., Heller, V. (2023). Numerical validation of novel scaling laws for air-water flows including compressibility and heat transfer. Journal of Hydraulic Research 61(4), 517-531 (https://doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2023.2225462). Catucci, D., Briganti, R., Heller, V. (2021). Numerical validation of novel scaling laws for air entrainment in water. Proceeding of the Royal Society A 477(2255) (https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2021.0339). Kesseler, M., Heller, V., Turnbull, B. (2020). Grain Reynolds number scale effects in dry granular slides. Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface 125(1):1-19 (https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005347). Heller, V. (2018). Two Replies to Discussions of „Self-similarity and Reynolds number invariance in Froude modelling“ by Ettema, R., and Sokoray-Varga, B., and Vladimir, N. Journal of Hydraulic Research 56(2):293;295-297 . Kesseler, M., Heller, V., Turnbull, B. (2018). A laboratory-numerical approach for modelling scale effects in dry granular slides. Landslides (open source). Heller, V. (2017). Self-similarity and Reynolds number invariance in Froude modelling. Journal of Hydraulic Research 55(3):293-309 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2016.1250832). Heller, V. (2012). Three Replies to Discussions of „Scale effects in physical hydraulic engineering models“ by Pfister, M., and Chanson, H.; Tafarojnoruz, A., and Gaudio; Echávez, G., R. Journal of Hydraulic Research 50(2):246; 248; 249-250. Heller, V. (2011). Scale effects in physical hydraulic engineering models. Journal of Hydraulic Research 49(3):293-306 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2011.578914). Heller, V., Hager, W.H., Minor, H.-E. (2008). Scale effects in subaerial landslide generated impulse waves. Experiments in Fluids 44(5):691-703 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00348-007-0427-7). Heller, V. (2007). Massstabseffekte im hydraulischen Modell. Wasser Energie Luft 99(4):153-159 (in German).

Others Heller, V. (2025). Analytical considerations about scale effects applied to landslide-tsunamis. Extended abstract for the Proceeding of the 41st IAHR World Congress 1882-1886 (https://doi.org/10.64697/978-90-835589-7-4_41WC-P1891-cd). Heller, V., Roy, D., Begam, S. (2025). Scale effects in 3D granular slides on a smooth incline. Extended abstract for the Proceeding of the 41st IAHR World Congress 1025-1029 (https://doi.org/10.64697/978-90-835589-7-4_41WC-P1963-cd). Begam, S., Heller, V. (2022). Experimental study towards the investigation of scale effects in 3D granular slides. Proc. EGU22. Catucci, D., Briganti, R., Heller, V. (2022). Analytical and numerical study of novel scaling laws for air-water flows. Proc. 39th IAHR World Congress, 4551-4560. Catucci, D., Briganti, R., Heller, V. (2021). Analytical and numerical study of novel scaling laws applied to a dam break flow. 16th UK Young Coastal Scientists and Engineers Conference, virtual, 29-30th March 2021.

|

|

The aim of the review articles Heller (2007, 2011) was to generically describe scale effects. The number of such generic rules applicable for all phenomena is limited. Scale effects are complex and depend on the involved forces and their relative importance changing from phenomenon to phenomenon. However, generally speaking: (i) physical hydraulic model tests with l (delta) ≠ 1 always involve scale effects; (ii) the larger l (delta), the larger are scale effects; each involved parameter requires its own judgement regarding scale effects (if the jet trajectory in Fig. 1(a) is not considerably affected, this does not exclude significant scale effects for air entrainment); (iii) and scale effects normally have a ‘damping’ effect, i.e. parameters such as relative wave height are normally smaller in the model than in its prototype. |

|

Four approaches help to obtain model-prototype similarity, to quantify scale effects, to investigate how they affect the parameters, and to establish limiting criteria where they can be neglected: |

|

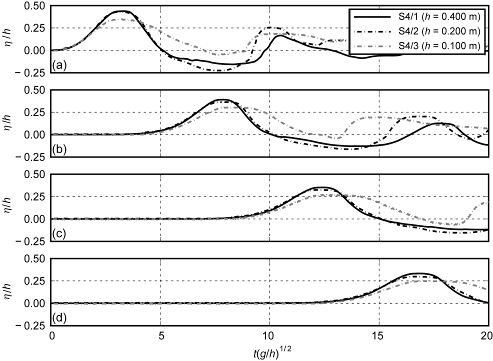

The scale series approach was applied in Heller et al. (2008) to define limiting criteria for scale effects in subaerial landslide-generated tsunamis/impulse wave. Tests involving granular materials were conducted at different scales as shown in Fig. 4. The employed wave flume was 0.50 m wide and the water depths were in the range 0.075 ≤ h ≤ 0.600 m. All parameters within a scale series were scaled according to Froude scaling, i.e. length scales were linearly reduced by the scale factor l (delta). Plotting the wave profiles for a scale series in dimensionless from (Fig. 5) results in a mismatch due to scale effects. With a total of seven scale series, it was possible to define that scale effects relative to the maximum wave amplitude are negligible (<2%) if: |

|

Fig. 5. Impulse waves scale series: normalized water surface displacement h/h (eta/h) versus relative time t(g/h)1/2 for three scales (Heller et al. 2008) |

|

In practice, scale effects are commonly avoided (with relevant rules of thumb, replacement of fluid, Fig. 2), compensated or corrected for. Some rules of thumb are the following (for a more comprehensive list with references see Heller 2011): |

|

· Wave propagation is affected less than 1% by surface tension if period > 0.35 s · Free surface water flows should be > 5 cm to avoid significant scale effects · Wave height for wave force on a slope during wave breaking should be > 0.50 m · Free surface air-water flows should be conducted at Weber number > 140 |

|

Fig. 2. Replacement of fluid: similar morphologies in sand caused by fluid (a) water: ripples in hydraulic model to investigate bridge pier scours, (b) air: ripples on sand dune (Heller 2011) |

|

· Inspectional analysis: model-prototype similarity criteria are found with an analytical set of equations describing the phenomenon. · Dimensional analysis: a method to transform dimensional into dimensionless parameters, which have to be identical between model and prototype. · Calibration: calibration and validation of model tests with real-world data (discharge, run-up height of tsunami). · Scale series: a method comparing results of models of different sizes (and different amounts of scale effects) in order to quantify scale effects. |

|

The parameter g is the gravitational acceleration, nw (nu) the kinematic viscosity, sw (sigma) the surface tension and rw (rho) the water density. The corresponding rule of thumb is h ≥ 0.200 m. |

|

Reynolds number R = g1/2h3/2/nw ≥ 300,000 Weber number W = rwgh2/sw ≥ 5,000 |

|

This part of Dr Heller’s research aims to exclude Reynolds number R scale effects in Froude models. Two concepts were identified for these purposes: (i) self-similarity and (ii) Reynolds number invariance. Figure 3 shows a simple example of self-similarity namely a Romanesco broccoli with a geometry identical to the geometry of a small fraction of itself. Similar, the self-similarity may also apply to fluid flows where the properties (e.g. velocity distribution) at small scale are identical to the properties at full scale, such that no scale effects are observed. Concept (ii) (R invariance) makes use of the fact that many fluid features at large R become independent of R. As R tends to increases with the model size, these independent fluid features are also observed at full scale (again no R scale effects are observed). |

|

Self-similarity and Reynolds number invariance in Froude Modelling |

|

The two concepts (i) and (ii) were reviewed and illustrated in Heller (2017) with a wide range of examples: (i) irrotational vortices, wakes, jets and plumes, shear-driven entrainment, high-velocity open channel flows, sediment transport and homogeneous isotropic turbulence; and (ii) tidal energy converters, complete mixing in contact tanks and gravity currents. The content of the forum paper Heller (2017) is summarised in a presentation available in the Downloads section. |

|

Last modified: 02.01.2026 |

|

Fig. 3. Example of a self-similar geometry in nature: Romanesco broccoli (Heller 2017) |

|

Landslide-tsunamis/impulse waves |

|

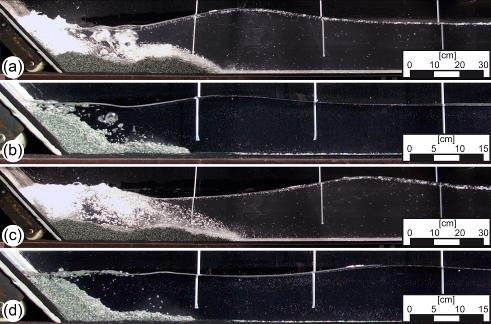

Fig. 4. Impulse waves scale series: test (a,c) conducted at half scale in test (b,d); the Froude number (inertial force/gravity force)1/2 is F = 2.5 for both scales while the Reynolds number R (inertial force/viscous force) and Weber number W (inertial force/surface tension force) differ between (a,c) R = 289,329, W = 5,345 and (b,d) R = 103,415, W = 1,336 resulting in different air entrainment and detrainment (Heller et al. 2008) |

|

Scale effects in granular slides (Dr Kesseler) |

|

Reynolds number (Re) dependence of scale effects |

|

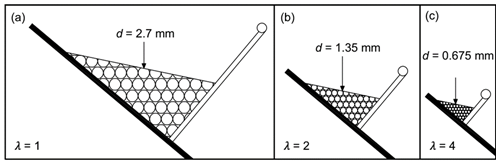

Scale effects have seen some focus in the field of fluid phenomena (Heller, 2011), but are less well known in granular contexts. In rockfalls, landslides, and avalanches, scale effects can manifest both in bulk slide properties such as velocity and runout, and in micro-scale interactions between particles. Particle fracture, stress variations, and particle size distribution can further complicate how scale effects manifest in these granular slides. In this study scale effects in dry granular slides involving quartz sand have been investigated, following a scale series of similar slides with constant design Froude numbers (Kesseler et al. 2018, 2020). Figure 6 details the initial release conditions of slides as the scale factor λ varies. Figure 7 shows the physical setup used to measure these slides in the laboratory, with slide masses of up to 110 kg. |

|

Fig. 6. Relative scaling of slide release wedges, channel, and mean particle diameter d varying with scale factor (Kesseler et al. 2020) |

|

Fig. 7. Laboratory setup including slide deposit at the medium scale |

|

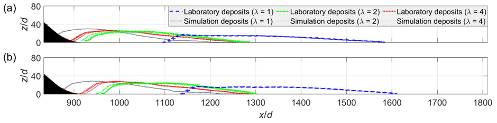

Significant scale effects were identified across the laboratory slides conducted in Kesseler et al. (2020), with the deposit runout distance x/d increasing by up to 26% as the scale increased and λ reduced. Figure 8 highlights this scale effect, with 2D sections at (a) the channel sidewall and (b) the channel centre. This difference in runout distance was accompanied by changes in the slide surface velocity, which increased by up to 35% across the scale range. These scale effects showed strong correlation to the grain Reynolds number (Re), suggesting that air-grain interactions are mainly responsible. Comparisons to discrete element method (DEM) simulations further confirmed this, as scale effects were not seen at all in simulations that did not include air flow. The particle drag force in particular was identified as a strong influence on these Re scale effects. Comparing the laboratory data of Kesseler et al. (2020) to that of other studies and slides in nature confirms that Re normalization is an effective way to quantitatively compare these slides of vastly different scales. |

|

Fig. 8. Comparison of laboratory and simulated nondimensional deposit thickness z/d over distance x/d at (a) 10% across the channel width and (b) 50% across the channel width (Kesseler et al. 2020) |

|

|